More is not merrier

Satyashri Mohanty

Economic Times August 27, 2014

Customers are spoilt for choice. Thanks to the explosion in variety in almost every consumer goods product category in the last few decades, they now have endless options before them. Be it for cars, coffee, capris or cell phones. They never had such a good time shopping. The good times only seem to be getting better, as multiple players continue to enter the market; and, older players reacting to the new offerings of their competitors, who, in turn, fight back with even more innovative products and services, and discounts. These are exciting times for sellers, too. However, with excitement comes pressure. The many functional teams – collectively called new product development organisations – involved in making new products are now under dual pressure to develop more products, and that too, faster to counter competition. The pressure goes up manifold in companies where the failure rate of new products is high.

The Disastrous Concoction: Load coupled with Uncertainty

In most new product development organizations, whether in auto or in consumer goods industry, adding of resources has not kept pace with increase of load. The enormous workload, highly uncertain environment of new product development, heavy dependence on external suppliers have together made the task of creating new products more challenging. The process is riddled with rework, delays in production stabilization, and delays in launch. Elevated stress levels of engineers is another serious concern.

Typical Solutions (that aren’t)

- More Resources

Operating managers in new product development perceive the core issue as a resource-capacity problem. They are convinced that cutting the number of active projects will aid execution of the selected few. However, this is the opposite of what top managements want. When there is intense competition, and the success of launches is uncertain, top managements want more, not less. The seemingly easy prescription – add more resources – is not viable as the ‘real’ expert resources are not easily available. Fresh-out-of-college graduates can add to the numbers, but not to effective capacity. The other ‘strategy’ – ‘let’s work-harder’ – does not help either. - More Visibility

Top managements of new product development organizations perceive the problem as a ‘visibility’ issue. This viewpoint owes its genesis to three control gaps:

- Issues interrupting progress are detected late(by those at the top) but get resolved quick after intervention.

- It is nearly impossible to pinpoint which department is responsible for the delays, the blame game never ends.

- The demands for more resources from many departments are never backed up with objective data on load and capacity. When output is low and almost every task is delayed, many at the top layer believe that resource groups are not productive enough.

These gaps lure auto or consumer goods organizations to buy tools that promise visibility by providing detailed project and resource scheduling. However, in an environment of frequent rework and scope changes, these schedules go haywire. With the need to frequently revise the project plans to keep them relevant, the entire scheduling exercise turns into an effort of hindsight correction – plans do not drive execution, they are merely revised based on what is already executed.

3. More Fast-Tracking

Frequent iterations and rework swallow capacity and time. Unlike in auto or in consumer goods manufacturing, the objective of zero rework and iteration will never be met in a new product development project (refer insert on type of iterations). However, it is well acknowledged that the later you identify the need for rework (or scope change), the more expensive and time consuming it is to carry out the rework. Managers are intuitively aware of the need to incorporate feedback of upstream and downstream departments early on, while work is being executed in a specific department. For example, it is crucial to incorporate feedback of marketing while the initial concept design is being finalized in the design department; this protects from expensive scope change requests later on. Similarly, it is important to incorporate critical inputs from production engineers while designing the product; this would make sure that the product is not only great, but also does not suffer from poor ‘manufacturability’. Often, teams have to move back and forth, which hinders project progress.

The following factors add to the complexity.

- Resource groups and managers are shared among different new product design and development (NPDD) projects.

- At the same time, they are supporting other non NPDD work.

- Every project is also executed in different phases (concept validation, product validation and process validation) and each department in the NPDD organization is involved in differing degrees in each phase. For example, design department is more involved when concept and product design is being finalized but its effort becomes low during production design.

Moving back and forth, especially in an environment where resources are shared across projects, creates frequent priority conflicts. These surface daily while making work allocation decisions. Questions like:

- Should the electrical design team work on its critical items or provide inputs for the mechanical design tomake a complete 3D model?

- Should procurement speed up the vendor decision to get the design inputs or take more time to negotiate the best price?

and many others are resolved based on the pressure of the day. Frequent priority changes increase the elapsed time of tasks, which builds time pressure. Departments resort to fast-tracking – handing over work without incorporating critical feedback. This approach of ‘fast-tracking’ projects only leads to wasteful rework and more delays.

The Core Issue

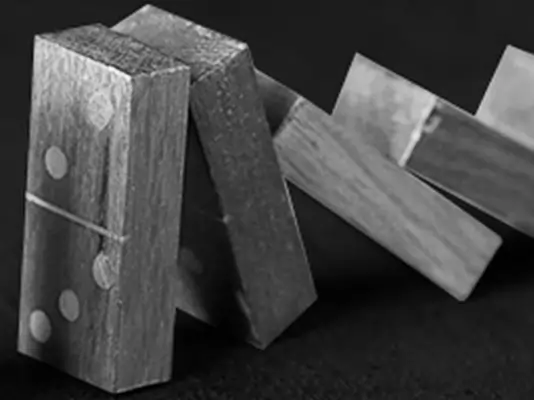

There is an interesting saying in the world of systems thinking: “When one wants to move the car faster, it is important NOT to violently push the accelerator further but to release the pressure on the brakes.” Many NPDD organizations in the auto or consumer goods industry are not aware that they actually have a foot on the brakes, even as they try to accelerate further. In this environment, the ‘foot-on-the-brake’ syndrome is the actions taken to expedite projects individually. When every project sponsor tries to move her project faster by setting aggressive task deadlines, the overall situation vitiates into cascading delays in other projects, which, in turn, forces other sponsors to push their projects with aggressive deadlines. The fall out is a vicious loop of delays and capacity watages.

Step 1: Releasing the brake

NPDD organizations in the auto or consumer goods industry are essentially multi-project environments where resources have to work across the phases of a project, and deal with many projects. At any point in time, there is a significant quantum of different and independent tasks available for a resource group to work on, both across projects and in different phases of the same project. At the same time, there is uncertainty in the environment. In such environments, upfront task scheduling is not only difficult but also damaging (activates the vicious loop mentioned above). So, the best way out is to learn from environments where this problem has been solved – the cash counter of a super market. A cash counter encounters two uncertain factors.

- The time taken to process the billing of an individual customer (as the number of items to be processed can vary).

- Arrival rate of customers to the cash counter.

No amount of analysis of past data can enable one to make a perfect schedule for the future. In such environments, operation managers do not resort to making schedules for individual customers. The counter does not, and cannot, work according to a pre-defined schedule. Instead, the managers put their energies into controlling work-in-progress (WIP) at the counter.

Customers queue up before the counters. At any point in time, there is only one customer at the counter (WIP Control). Only when her bill is complete does work on the next bill begin. When the queue grows longer, efforts are made to speed up billing but the rule of ‘completions-triggering-start’ is never violated.

The take-away from this environment is that WIP control along with queue management is the only way to trigger work in an uncertain environment with shared resources executing independent projects.

WIP control (a flow regulating mechanism) has been used effectively in production environments, especially in the auto industry. Kanban cards, and the concept of limiting space has been deployed effectively to prevent piling of inventory between workstations to speed up flow. Even in job shop environments without these artificial limitations, the pressure on controlling WIP is always high, because WIP is visible, and is reported in financial statements. Many job shops focus on accelerating the flow by flushing out excess inventory towards month-end, when financials are reported. So production environments have some flow enhancing mechanism of controlling the incoming rate to improve the outflow of completions – WIP management.

However, WIP management is neglected in NPDD environments – even in the auto industry, primarily because it is usually invisible for long periods. Drawings stored on hard disks are not out in the open like WIP on the shop floor of an auto plant. Even the WIP of physical components at geographically spread out vendors is not visible collectively. There is never a problem of space to keep multiple projects open, as these open projects do not impact financial statements. The lack of WIP regulating mechanism is the reason for flow problems in NPDD environments.

The way to improve flow here is to put aggressive WIP limitations in every critical resource group. Only when the specific work module meets the agreed closure criteria, should another work module from the queue be allowed in – the ‘one in and one out’ rule of the cash counter.

WIP norms need to be set for every critical department for pre-defined task modules with clear closure criteria. (This is different from the lean production approach of restricting work between resource groups, and, at the same time, throttling the work input to the overall line. Here, the focus is on restricting the number of tasks being worked upon inside a resource group).

This step requires three other supporting paradigms of management:

- Upfront definition of closure criteria of work modules. This is never to be violated.

- Agreement on common priority system of projects; projects get a queue number. Tasks are picked up in the order of their queue numbers.

- Daily management to resolve issues interrupting progress of task modules in WIP to prevent queue build up.

A common priority list creates a common understanding of what is truly urgent. It helps synchronize efforts of different new product development resource groups. At the same time, the rule of ‘one in and one out’ reduces wastage resulting from switching. The rule of meeting closure criteria prevents type 1 (fast tracking) errors. Daily management ensures issues are identified and resolved early.

The combined effect is a dramatic release of capacity and reduction in lead-time of new product development. This reduction further enables one to hold on to the critical rules of strong gates at project and module level. For example, a rule of completing the 3D model in its entirety before releasing to detailing can be implemented only when time taken to complete the 3D model comes down dramatically.

Step 2: Push the Accelerator

When the queue becomes visible, the load and capacity is revealed for the entire organization, leading to further improvements such as multi-skilling in critical departments with longer queues. The combined effect of initial steps and improvement efforts usually releases capacity to the extent that the queues become shorter than the WIP norm in various resource groups. The rule of WIP norm needs enforcing in very few resource groups. As the leadtime reduces for all projects, and queuing delays are restricted to a few resource groups, it is crucial to start managing individual projects in the time domain to prevent work expansion at a resource level.

However, if one tries to schedule task milestones, there is a chance of one activating the vicious loop of rampant re-prioritization. In this environment of scope and task time uncertainty, there is no need to be precise with detailed project plans. Projects can be planned with ‘touch time’ clearly demarcated from the total time; the remaining time is set aside as common project buffer to absorb the uncertainty in execution. The touch time is uninterrupted work time of the task modules. Once work is initiated on a specific project, and variability of the environment kicks in, one gets to know the rate of buffer consumption as compared to the rate of work completion. This analysis across many projects also helps in changing priority in waiting queues. It also provides the much required visibility and control on progress of overall projects. The visibility not only helps bring top management attention to unresolved issues, but also provides objective information about departments where buffer burn out rate is consistently high.

Many new product development organizations in India, particularly in complex auto and consumer goods environments, have started adopting the above flow principles, setting up new industry benchmarks in lead-time and output.